A review of the "homeless" issue in Chico, CA

8 years in, this is how I see things on this topic

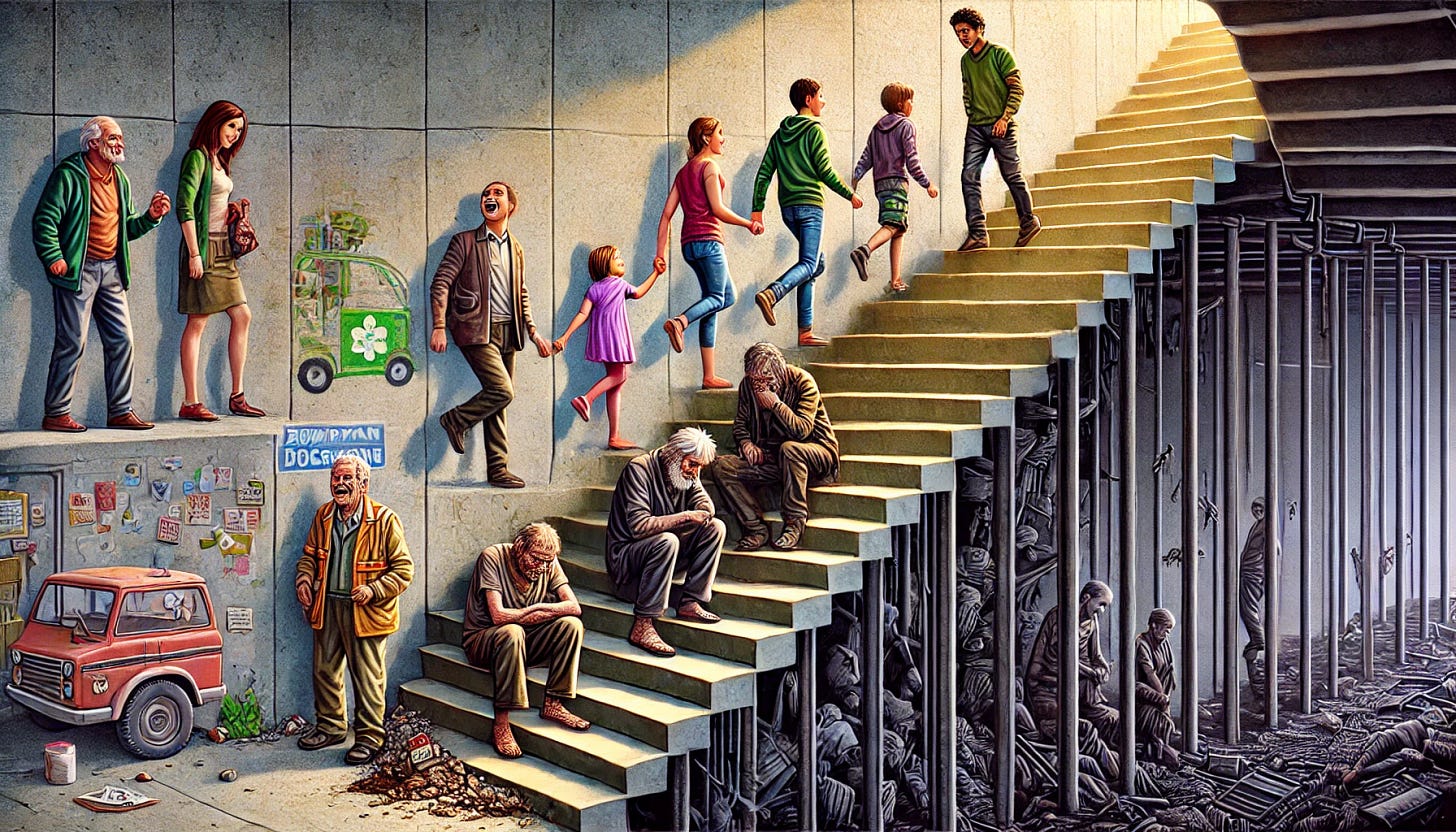

Chapter 1: Misdiagnosis of the Problem

The State’s Obligation to Care for Indigents

California's Welfare and Institutions Code[i] explicitly outlines the State and counties' duty to care for indigent individuals who lack the capacity to provide for themselves. This legal framework once ensured that those suffering from severe mental illness, substance abuse, or other incapacitating conditions were either institutionalized or enrolled in state-funded programs if they had no family to assist them. Institutional care—whether through mental health facilities, deferred drug treatment programs, or correctional systems—served as the foundation for addressing the needs of society's most vulnerable.

In practice, this system was designed to balance public safety, individual accountability, and compassion for those unable to care for themselves. When individuals refused to participate in treatment programs, adequate capacity in jails or prisons provided a last-resort safety net to prevent those with untreated conditions from endangering themselves or the community.

The Overwhelming Scope of Co-Morbidities

Today, the composition of California’s homeless population reflects the dismantling of these systems. It is estimated that approximately:

80% of the homeless population suffers from substance abuse.

50–60% experience untreated mental illness.

50% or more grapple with multiple co-morbidities, such as chronic health issues exacerbated by addiction or mental health conditions.

These staggering figures point to an intersection of challenges that require specialized, coordinated intervention—not simply temporary shelter or surface-level services. Yet, California’s policies have evolved to fundamentally misdiagnose homelessness as primarily an economic problem rather than a complex interplay of health, legal, and social factors.

The Civil Rights Shift

Over the past few decades, California's governance underwent a paradigm shift in its approach to homelessness. As a supermajority in state government emerged, the focus transitioned from compulsory care for the incapacitated to a rights-based framework that treated conditions like addiction and mental illness as civil liberties rather than medical or social emergencies. The right to refuse services became sacrosanct, even when individuals' decisions perpetuated cycles of harm to themselves and society.

This ideological shift culminated in the adoption of the "Housing First" policy, which prioritizes providing housing without requiring individuals to engage in self-improvement programs. Proponents argue this approach stabilizes the homeless population by providing basic needs; however, critics highlight its failure to address root causes like addiction, untreated mental health issues, and the personal accountability needed for long-term change.

The Creation of the Homeless Industrial Complex

To implement the state’s evolving policies, California took advantage of the HUD-mandated establishment of Continuums of Care (CoCs) in each county. These entities function as grant-fund distribution centers, with recipients also serving on the boards who distribute funds to themselves and colleagues. CoCs are theoretically responsible for coordinating services to the homeless population, however they actually have become unaccountable distribution centers for the various NGOs that comprise the homeless services industry. While their role ostensibly involves addressing homelessness, the framework prioritizes compliance with the policy frameworks and delivery of program services, with few obligations for demonstrating measurable outcomes.

The CoCs are governed by the non-governmental organizations (NGOs) they fund, largely unregulated by local jurisdictions. Unlike private industries subject to local oversight and regulations, these organizations operate independently, with their performance tied solely to the terms of state grant agreements. Success is measured not by reductions in homelessness but by the number and type of services offered. This metric incentivizes expanding service availability—sometimes at the expense of real progress.

For example, a county might allocate millions of dollars to an NGO that provides counseling, meal services, and temporary shelter but does not address systemic barriers to recovery, nor report positive outcomes resulting from services offered. Often, while services might be available, there is no mechanism to compel participation.

Meanwhile, executive directors of these NGOs often command six-figure salaries, while volunteers and entry-level staff carry out much of the day-to-day operations. This structure creates a moral hazard, where reducing homelessness—ostensibly the goal—threatens the funding that sustains these organizations. As a result, the "Homeless Industrial Complex" emerges: a self-reinforcing ecosystem where state grants and NGO operations depend on maintaining or even growing the homeless population.

In addition to the moral hazard of the NGOs, the state cynically understands that if the responsibility for indigent care shifted back from the NGOs to the state, the state would be obligated to make an enormous investment in state service institutions: drug rehab, mental health, and incarceration. The state is strongly interested in keeping this deception going to avoid these obligations.

The Consequences of Misdiagnosis

The focus on housing and service provision without accountability has yielded disastrous outcomes in many communities. Homeless encampments persist or grow, public safety deteriorates, and residents face increasing frustration with the lack of visible progress despite the billions of dollars funneled into these programs. This systemic failure reflects not only a misdiagnosis of the problem but also the entrenchment of financial and political interests in perpetuating homelessness rather than solving it.[ii]

Chapter 2: Enabling Factors and Legal Obstacles

The Expansion of the Homeless Industrial Complex

As the Homeless Industrial Complex grew, it supported one of California’s largest industries, with annual budgets approaching $20 Billion/year, yet it operated with minimal regulation by local jurisdictions. This lack of oversight allowed non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and Continuums of Care (CoCs) to act as quasi-autonomous agents of state policy. Freed from the accountability measures typically applied to private industries or local government programs, these entities enjoyed unparalleled latitude in managing their operations and funding allocations.

The financial incentives inherent in this system often perpetuate homelessness rather than reduce it. Grant recipients faced pressure to sustain or expand the population they served to justify continued funding. This dynamic created what critics describe as a self-reinforcing cycle: the larger the homeless population, the greater the demand for services—and the greater the revenue for the organizations providing them.

At the same time, this framework unintentionally enabled the homeless population. Services such as free meals, shelters, and medical care were provided without requiring individuals to address the root causes of their homelessness, such as substance abuse, mental illness, or chronic criminal behavior. By prioritizing harm reduction over accountability or recovery, the system not only failed to incentivize change but, in many cases, normalized and sustained dysfunctional behaviors.

Lawfare: Martin v. Boise and Johnson v. Grants Pass

Compounding these challenges was the rise of lawfare—a legal strategy that used lawsuits to limit the enforcement authority of local governments. Two landmark cases, Martin v. Boise and Johnson v. Grants Pass, redefined the legal landscape for cities attempting to address the impacts of homelessness.

Martin v. Boise (2018): This Ninth Circuit Court ruling determined that it is unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment to enforce anti-camping ordinances if adequate shelter beds are not available. While this ruling was ostensibly designed to protect the rights of homeless individuals, it had far-reaching consequences. Cities were forced to prioritize the creation of shelter beds—a costly and logistically challenging endeavor—before enforcing laws against public camping. Many jurisdictions lacked the resources to comply, effectively leaving encampments unchecked.

Johnson v. Grants Pass (2022): This ruling expanded on Martin v. Boise, holding that fines or penalties for sleeping outdoors in public spaces could also violate constitutional protections if no viable alternatives were available. This case further constrained cities’ ability to manage encampments, emboldening advocates and lawyers to challenge enforcement efforts through lawsuits.

These rulings created a climate of legal uncertainty that paralyzed local governments. Lawsuits were filed, judgments rendered, and settlements negotiated in ways that often stripped cities of their traditional enforcement authority. As a result, cities faced "adhesion contracts" that required them to adopt policies dictated by legal precedent and advocacy groups, effectively relinquishing control over public safety and quality of life to outside forces.

Very few cities followed the examples of Boise or Grants Pass, both of which fought this trend of enforcement power transfer to plaintiffs in the homeless population, and the settlement agreements arising as a consequence. While both of these cities carried their battle all the way to the Supreme Court, the Court refused to intervene in Boise until the favorable ruling for cities resulting from the Grants Pass case.

Unfortunately, cities like Chico, which had entered into binding settlement agreements, were bound by those agreements despite the Grants Pass favorable ruling. In Chico’s case, a Rule 60 motion for relief based on the changed circumstances reflected by the Grants Pass decision has been pending in Federal Court for months. Meanwhile, the city remains paralyzed in its enforcement efforts.

The Erosion of the Penal Code

In parallel with the rise of the Homeless Industrial Complex and the limitations imposed by lawfare, the State of California had implemented sweeping changes to its penal code. These reforms, including AB 109 and Propositions 36, 47, and 57, fundamentally altered the state's approach to crime and punishment:

AB 109 (2011): Known as "realignment," this law shifted the incarceration burden from state prisons to county jails. It aimed to reduce the prison population but resulted in overcrowded county jails ill-equipped to handle the influx. To manage capacity, local authorities adopted "catch-and-release" practices for non-violent offenders, effectively weakening the deterrent effect of incarceration.

Proposition 36 (2012): This measure revised California's "Three Strikes" law to reserve life sentences for violent offenders. While it reduced prison sentences for many non-violent offenders, it also removed a critical tool for addressing recidivism among habitual criminals, many of whom struggled with substance abuse or mental illness.

Proposition 47 (2014): This initiative reclassified several felonies, including certain drug possession and theft offenses, as misdemeanors. Critics argue that this reduced accountability for petty crimes, emboldening repeat offenders and undermining public safety.

Proposition 57 (2016): This measure expanded parole opportunities for non-violent offenders and gave prison officials more discretion to award early release credits. While intended to reduce prison overcrowding, it further eroded the state’s ability to address chronic criminal behavior.

These reforms collectively dismantled key components of California's criminal justice system. They de-emphasized incarceration as a means of addressing addiction and mental illness, eliminated deferred drug court programs, and reduced the consequences for property and drug-related crimes. In doing so, they exacerbated the challenges faced by local governments, which were left to manage the fallout.

The Consequences for Local Jurisdictions

The combination of legal constraints and penal code reforms left cities in Northern California—and across the state—ill-equipped to address the impacts of homelessness on their communities. With limited enforcement tools and overcrowded jails, law enforcement agencies became increasingly constrained in their ability to respond to public complaints about theft, vandalism, and encampments.

For the 99% of residents who are not indigent, these policy failures translated into declining public safety and quality of life. Business owners struggled with theft and property damage, families avoided parks and public spaces overrun by encampments, and neighborhoods faced the health risks posed by unsanitary conditions and open drug use.

Meanwhile, the state's emphasis on "housing first" and harm reduction, coupled with the unchecked growth of the Homeless Industrial Complex, perpetuated a system that prioritized short-term solutions over meaningful reform. For many cities, the question was no longer how to solve homelessness but how to mitigate its growing impacts on their communities.

Chapter 3: Consequences in Chico, California

Safety, cleanliness, beauty, and economic vitality circle the drain

The combined effects of state policies, judicial rulings, and the unchecked growth of the homeless industrial complex took a significant toll on the city of Chico, California. These consequences were not abstract—they manifested in visible and devastating ways, reshaping the city’s character and livability.

Encampments and the Influx of Homeless Individuals

Large and growing encampments began to appear in Chico’s public parks, plazas, and sidewalks. Social media platforms such as Reddit and other forums became conduits for transient individuals to share information, designating Chico as a "good" destination for the homeless due to lenient policies and abundant resources. What began as localized issues quickly ballooned as out-of-town and out-of-state homeless individuals flooded the city.

This influx of homeless indigents was exacerbated by the Camp fire that devastated Paradise and the consequences of the Covid pandemic, both helping to attract those perceiving an opportunity in the outpouring of community charity.

A sympathetic city council majority, influenced by pandemic-era rhetoric, issued a directive suspending enforcement of anti-camping ordinances. This decision, framed as compassionate and justified under COVID-19 emergency measures, allowed the encampments to grow unchecked. The suspension of enforcement provided safe havens for squatters, and public spaces became increasingly commandeered by encampments.

Shift in Political Will and the Whack-a-Mole Effect

When subsequent elections shifted the council majority’s stance, enforcement efforts resumed, sparking protests and backlash from the "homeless industry." Advocacy groups, often driven by ideology or financial incentives tied to state policies, criticized the renewed enforcement. By this point, the encampments had grown large, destructive, and unmanageable. Clearing one area only caused populations to surge in others, creating a frustrating and futile "whack-a-mole" dynamic.

The Warren Settlement: A Pivotal Turning Point

Faced with mounting public pressure and legal challenges under Martin v. Boise, the city was sued and all enforcement was halted pending the outcome. That injunction ultimately resulted in the unfavorable Warren Settlement. This agreement forced Chico to:

Curtail enforcement of camping bans by requiring a generous notification process, subject to legal procedures for objecting to enforcement plans, causing long additional delays.

Divert millions of dollars to construct one of the nation’s largest shelters, with a capacity of up to 344 beds.

Implement a slow, piecemeal approach to clearing public spaces, only for those spaces to be reoccupied soon after.

The settlement placed Chico under the jurisdiction of a federal magistrate sympathetic to plaintiffs and the "homeless campus" model. His rulings frequently restricted the city’s ability to act, exacerbating an already dire situation.

The Domino Effect: Crime, Drug Abuse, and Social Decay

The consequences of the settlement and Chico’s broader homelessness crisis were profound and multidimensional:

Crime Surge: Shoplifting, assaults, and antisocial behavior became routine. Criminals with outstanding warrants used Chico as a haven, blending into the transient homeless population. Others, including individuals with stable homes and jobs elsewhere, came for "drug vacations" among the homeless population, where drugs were readily available.

Drug Epidemic: Drug overdoses became a common occurrence, claiming the lives of homeless individuals and even local teenagers who obtained drugs from the camps. The tragic death of Tyler Rushing, following a drug-induced psychosis and confrontation with police, epitomized the chaos.

Public Spaces Rendered Unusable: Parks, plazas, and sidewalks became inhospitable to residents, particularly families. Downtown Chico, once a vibrant hub, was effectively "off-limits" to shoppers and visitors seeking to avoid encounters with drug-addled or mentally unstable individuals.

Wildfires and Arson: The homeless crisis compounded the city’s vulnerability to disasters. In one notable tragedy, an arsonist—roaming freely among the encampments—set fire to Chico’s historic Bidwell Mansion, reducing it to ashes. The fire went unreported until it was too late to save the landmark. Another habitual criminal out on parole started the Park Fire, which devastated parks and communities well beyond its local origin in Bidwell Park.

Legal Paralysis and Lingering Impacts

The Supreme Court’s decision in Grants Pass offered a glimmer of hope for municipalities grappling with Martin v. Boise-related constraints. Since Chico was bound by the terms of the Warren Settlement, the city filed a Rule 60 motion to modify the settlement terms in light of the new precedent. However, the motion languishes in federal court, leaving the city in legal limbo.

Compounding the issue, the city attorney interpreted the Warren Settlement so broadly that enforcement of basic laws—such as littering or public intoxication—was effectively prohibited against anyone in the homeless population, while “housed” citizens remained vulnerable to enforcement. This set up a new “protected class” of citizens based on the condition of “homelessness” and this even found its way into official city ordinances, where the “homeless” were expressly exempted from enforcement. This legal paralysis left the city unable to maintain basic public order, further entrenching the crisis.

The Social Cost

The human and social costs of these policies were devastating:

Erosion of Public Trust: Residents grew disillusioned as they witnessed their city transform into a haven for lawlessness.

Violence and Exploitation Within Homeless Communities: Rape, robbery, and violence became common within the homeless population itself.

Psychological Toll: Families, children, and long-time residents bore the brunt of the crisis, feeling increasingly unsafe and disconnected from their community.

Chapter 4: Recommendations

A Historical and Practical Framework

Historical Context

For centuries, societies have acknowledged the existence of individuals who lack the capacity to fully conform to social norms due to age, disability, mental illness, economic hardship, or criminal tendencies. In response, governments and communities have developed systems of care designed to balance compassion with social order.

Historically, our humanitarian efforts have evolved: debtor prisons, inhumane asylums, orphanages, and brutal penal systems have been replaced with programs emphasizing rehabilitation, humane treatment, and social reintegration. These advancements reflect a collective understanding that humane, state-funded solutions are essential to addressing incapacities while maintaining public safety and societal cohesion.

The principle of graduated responsibility and accountability has guided many of these reforms. For instance, not all individuals with incapacities require the same level of intervention. Similarly, offenders can be evaluated and placed on a spectrum of accountability, ranging from rehabilitation programs to incarceration, based on their capacity and willingness to adapt to societal norms.

The Role of the State and Counties

The California Welfare and Institutions Code assigns the responsibility for addressing incapacities to the state and counties—not municipalities. This division of responsibility recognizes that the scale and complexity of these issues are best addressed through centralized funding, oversight, and administration, allowing for more consistent standards and equitable distribution of resources.

However, the current system has failed to meet these responsibilities adequately. Cities like Chico are left bearing the burden, forced to grapple with the consequences of policies that prioritize ideological solutions over practical ones. To realign these responsibilities, the state must:

Provide Adequate Facilities and Programs: Establish a network of shelters, treatment facilities, and correctional institutions that meet the needs of individuals across the spectrum of incapacity.

Ensure Consistency in Enforcement: Mandate that all jurisdictions adhere to consistent standards of enforcement, ensuring that cities are not left vulnerable to encampments, crime, and social disruption due to gaps in state and county services.

Contact, Enforcement, and Accountability

Building on historical principles and modern realities, the official policy for addressing homelessness and related issues should focus on three pillars: Contact, Enforcement, and Accountability.

1. Contact

The first step in addressing homelessness and incapacity is proactive and compassionate engagement. Every individual living on the streets must be contacted, identified, and evaluated by professionals trained to assess their physical, mental, and criminal capacities. Key elements of this process include:

Identification and Evaluation: Establishing the identity of each individual and evaluating their circumstances, including health, substance use, and criminal history.

Professional Assessment: Deploying teams of mental health professionals, social workers, and law enforcement to determine the most appropriate intervention for each individual.

2. Enforcement

Enforcement of laws and social norms is critical to restoring order and creating pathways for rehabilitation. When laws are consistently enforced, individuals are more likely to seek assistance and comply with rehabilitation programs. Key recommendations include:

Graduated Enforcement: Implementing programs like drug courts, mental health diversion, and probation to provide alternatives to incarceration for individuals willing to engage in rehabilitation.

Non-Negotiable Accountability: For those who fail to comply with diversion programs or continue to disrupt public order, enforcement must be swift and certain. Consequences may include incarceration, compulsory treatment, or other appropriate measures.

Ending the “Catch-and-Release” Cycle: Ensure that violations of laws, including those related to drug use, theft, and encampments, are consistently addressed to prevent cycles of recidivism and social harm.

3. Accountability

Accountability must apply to all parties involved in the system, including individuals, agencies, and policymakers.

Personal Accountability: Individuals receiving assistance or participating in diversion programs must adhere to clear expectations and consequences. Breaking the promise to change should result in immediate enforcement actions.

Program Accountability: Agencies and institutions responsible for implementing these policies must be held to measurable outcomes. Metrics such as reduced recidivism, increased program compliance, and improved public safety should guide funding and policy decisions.

Transparency in Oversight: All decisions, funding allocations, and enforcement actions must be transparent to the public, ensuring trust in the system and deterring misuse of resources.

Conclusion

The challenges faced by cities like Chico are not insurmountable, but they require a shift in perspective and policy. By realigning responsibilities to the state and counties, implementing a structured program of Contact, Enforcement, and Accountability, and holding all parties to clear standards of conduct and outcomes, it is possible to restore order and dignity to communities while addressing the root causes of homelessness and incapacity.

Ultimately, the goal must be to create a system that is humane, effective, and sustainable—one that balances compassion with accountability and ensures that no individual or community is left to bear the burden of inaction.

[i] Welfare and Institutions Code §17000:

"Every county and every city and county shall relieve and support all incompetent, poor, indigent persons, and those incapacitated by age, disease, or accident, lawfully resident therein, when such persons are not supported and relieved by their relatives or friends, by their own means, or by state hospitals or other state or private institutions."

[ii] PRA-20250125-56244 requesting records of Butte County funding history

Thanks!!