In the West, we take sitting in chairs for granted, as we should. Anyone traveling to East Asia realizes using chairs for sitting is not the norm.

Some say this has to do with cultural values. In Japan, it is said that sitting near the ground symbolizes groundedness and humility. This is further reflected in the ritual of bowing as a show of respect to others. Social status and deference are shown to others by bowing lower than those “above” you, not by sitting in a taller chair above others, even if you were the Shogun. You demonstrated your status by seating yourself farthest from the door.

In Western culture, we show respect by standing tall. The taller and straighter we stand, the more deferential and respectful. A Private stands at attention in the presence of a General, head up, shoulders back, chest out, spine straight. The salute is the proper greeting gesture in the military but in civilian life, we touch through the familiar handshake, or a hug when greeting a friend. In Eastern culture touching is avoided.

But there is a compulsive similarity. If you extend your hand to someone, they will reciprocate, and you will shake hands. Many cultural signals are communicated through this ritual. If you want to start a fight, try refusing to shake someone’s hand. Remember the scene in Tjango, where Calvin Candie forced King Shultz to shake his hand, he refused, and it resulted in a gunfight. That is how powerful this ritual is. Likewise, if a Japanese man bows to another, the response is automatic, or there will be unpleasant consequences. You show defiance by bowing less low than you should.

Perhaps a more practical explanation exists for why we use chairs in the West and not the East. Climate cannot explain the difference, since the summer weather in Asia and the Eastern and Southern U.S. has many similarities.

Craftmanship was also an issue. As any woodworker knows, engineering and constructing a solid, comfortable chair is no trivial task, but Japan didn’t lack the necessary woodworking skills.

In pre-Renaissance Europe the peasant class sat on stools, benches, chests, or skins and mats, while the ruling class enhanced their status by raising themselves above the others on a throne. Serfs stood in their presence. Village taverns sported long benches to accommodate many people before a table.

In Europe, chairs gradually became more common in homes as society embraced individual comfort, especially from the Renaissance onward. Chairs had initially been symbols of status and authority, but by the 17th and 18th centuries, they became more accessible to the middle class. The Industrial Revolution of the 18th and early 19th Centuries made chairs accessible to nearly everyone.

In Japan, however, there was little parallel development in seating; traditional floor-sitting furniture, like tatami mats and zabuton cushions, was preferred, aligning with Japanese cultural norms of modesty and humility. This period also corresponded with Japan’s isolationist policy, which began in the 1630s under the Tokugawa shogunate and lasted until 1853, with the arrival of American Commander Mathiew Perry.

Even when Japan began embracing Western technology and trade, and the current modernization of Japanese culture, the adoption of Western chairs was limited to business and government operations. If you visit Japan today, office workers sit in chairs in front of raised desks, like the West, but at home or in a restaurant, you don’t sit in chairs. As was a Westerner who has never been able to cross my legs, it nearly killed me.

Once at a Japanese restaurant, I was terribly uncomfortable sitting on the floor. My Western habits didn’t translate well. To relieve my back and joints, I sat on my knees, with my butt resting on my lower legs. This was a social faux pas, I quickly learned, as this seating posture was strictly reserved for formal settings, like a wedding or a tea ceremony, and it was inappropriate for sitting with colleagues. To adapt to people like me, restaurants began putting “pits” below tables so Westerners could hang their legs over the edge. Quite a clever innovation.

Somewhere in the evolution of seating and chairs, a rocker was placed on the legs of a chair, and the rocking chair was invented. The use of rocking furniture, however, came long before the invention of the rocking chair. Rocking cradles were used in ancient Egypt and Rome, and rocking horses were common toys, especially for the well-to-do but not exclusively.

If rocking soothed the babies into sleep, and entertained budding horsemen, why not soothe and entertain ourselves? Thus, the rocking chair was born.

In the Victorian Era, rocking chairs offered a soothing, gentle motion that was especially appealing to women for activities like reading, sewing, or knitting. The Victorian parlor, the site of high teas and other forms of socializing offered comfortable seating including rocking chairs.

Victorian women spent considerable time caring for infants and young children, and the rocking chair became a convenient piece of furniture for calming and feeding babies. This association with comfort, domesticity, and motherhood made the rocking chair a staple in many Victorian parlors. It was often upholstered and designed with ornate carvings, reflecting the Victorian taste for decorative and elegant furniture.

In the Deep South, the summers are brutally humid and hot, very similar to Japan’s. A covered porch was a standard feature of most Southern houses. Mississippi dogs sleep under the porch, but people sit upon them. A common design for southern houses, especially farmhouses, included a central hallway serving as a breezeway connecting the front and back porch. The back porch was screened to keep the bugs out of the adjoining kitchen. The front door also had a screen door, and the purpose of the hallway was to pick up any cooling breeze and distribute the cooler air throughout the house.

It's fair to say that we should thank the American South for the tradition of placing rocking chairs on the porch. The South’s warm climate and cultural emphasis on hospitality made the porch a natural extension of the home’s living space, where people could relax in the breeze, socialize with neighbors, and observe the world around them.

Rocking chairs, with their soothing motion and comfortable design, fit perfectly into this setting and became an iconic part of Southern porch culture. The porch swing was also common for the same reason. Not only was the rocking motion soothing, but it also created a breeze on your face. In the hot humid South, rocking and fans were also used together. Rocking and fanning, rocking and fanning. I’ve often watched my Grandma, Aunts, and Cousins do both.

In the South, if someone you knew walked by while you were in your porch rocker, you would likely invite them to “come on up to the porch and sit awhile.” Most southern porches didn’t have just one or two, but several rockers arrayed on the front porch, enough for family and visitors. It would be a social embarrassment to not have an empty place for a visitor to sit.

In my many trips to Prentiss, Mississippi, rocking chairs and porches were among the many things that made me realize I wasn’t in Stockton, California anymore. The front porch is where adults caught up on the news, shelled black-eyed peas for dinner (the large, lunch meal) and relaxed after supper (the evening meal made up of leftovers from dinner).

In 2004, we made our last visit “home” as my dad used to call our Mississippi trips with the California family. This is mom, and these are my two daughters and four nieces sitting on the porch of my Great Uncle’s home.

I have several rockers in my home. One belonged to my mom, one to her mother, and one from Uncle Jake’s porch in Mississippi. Here is the story of that one particular rocker.

As I have previously explained, my dad grew up on a farm, and his dad and several generations before him were farmers. Grandpa was typical of many white farmers in Mississippi. No one in our family ever owned slaves or large plantations. That was mostly something only the rich plantation owners did. Though my great-grandfather’s generation had a direct memory of the Civil War, by the time my dad came along in 1916, emancipation was a distant memory. The racial divides in my family history were typical, but not stereotypical.

My grandfather employed 5 share-cropper families, and my dad played mostly with their children growing up, hunting rabbits and doing other normal childhood things. They used a throwing stick to kill rabbits because bullets cost money. In those days the essentials of life were plentiful, and Dad’s family earned some cash selling cotton and butter. Prentiss was fundamentally a subsistence economy, but not poor. Life was not easy, but the essentials were abundant, and expenses were low.

Men like my grandfather and his father before him farmed, and were successful enough over the years to build a nice house, buy enough land to support hired help, and sell cash crops, both to the locals and in the case of cotton, to regional and international markets.

They always had a large truck garden, and Grandma and her youngest helper, my dad, would bring okra, corn, and black-eyed peas from the garden in the morning to the dinner table at noon. Sweet potatoes would go into the root cellar for use over the winter, and, their butter from their milk cows and churned on the porch by my father, had a hidden secret flavor. Women stood in line for John Berry’s butter every Saturday, and no one could guess why it tasted so much better than the rest. It was sweet potatoes. Grandpa secretly fed sweet potatoes to his cows.

Every spring, a man who owned two mules would make the rounds plowing people’s gardens for the spring and turning them over in the winter. Others would chop, split, and deliver stovewood. When someone slaughtered a beef or pig, portions would be traded around with the neighbors, who did the same when they slaughtered one of theirs.

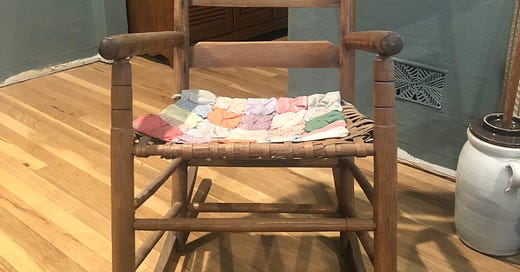

Another man, whose name is long forgotten, would spend the winter making rocking chairs out of hickory, the local hardwood. He had a small water-powered lathe to turn the rails and styles that made up the back, seat, and legs. He curved thinner pieces of hickory for the back slats by boiling them in water and bending them over a mold. The pieces fit together with crude, hand-carved mortise and tenon joints, secured with small iron nails.

The rockers were sawed to their shape from a wide board, and finished and smoothed on the bottom with a rasp. The legs were then fitted with overlapping joints against the rockers and nailed. The seat was woven from strips of green hickory bark. When dried, it was hard and durable, but the weave gave way to the shape of the human bottom. This chair is at least 100 years old, purchased around when my dad was born. The original seat is still intact.

The maker of this chair would pile several up in the back of a wagon pulled by a single mule and carry them from farmhouse to farmhouse offering them for sale. My grandfather bought many of them over the years, including this one.

I first saw this chair on the porch of my Uncle Jake and Aunt Wilda. They had taken over the house belonging to Grandpa When Grandpa died, and Grandma Ella lived with them in that house until she died. As a child, I remember her sitting on the porch shelling a big bowl of black-eyed peas that would be cooked for dinner. She would show us how to do it and we would help.

I can see her all these years later, a bowl in her aproned lap, rocking gently back and forth, gnarled fingers snapping pea pods she held in a bunch in her hand, her fingers deftly dropping the shelled peas into the bowl. Our culture had not invented the phrase “farm-to-table” yet, but when it became popular in the lexicon I thought of Grandma and Aunt Wilda.

My Mississippi people got old, as people do. First Grandpa died in 1962 after suffering from severe dementia and living in town with his oldest son. Dad traveled back to Mississippi on his own to attend the funeral.

Most of what was in the family was already spread around to the uncles and cousins who still lived back there, but Dad brought home a couple of items belonging to his parents. My older sister got a wind-up chiming mantle clock that sat on their mantle for years. My younger sister got an ancient treadle sewing machine that still worked.

I remember the day he returned from that trip. Looking back, although at the time I was oblivious, I realized that Dad must have felt some sadness that there wasn’t anything for me. It hadn’t occurred to me to feel left out. But Dad must have thought I did, so he made a private, solemn occasion of giving me the gold watch his father had given him for high-school graduation, and his navy ring. I have the ring, but not the watch. That is another story entirely.

Grandma died in July of 1971. Our family was already scattered to the wind, and Mom and Dad were unable to attend the funeral. My cousin, Paul, was planning on driving back for Grandma’s funeral, and Dad spoke to him before he left.

My father was much closer to Grandma than Grandpa for many complicated reasons. One was because as a young boy, his job was to do chores for Grandma around the house, while the older two brothers worked with Grandpa farming. What my dad wanted, the only things he mentioned, were three things. There was a single-shot 22 that he used as a kid. It was a miniature version of the adult model, made for youngsters. All of his brothers took turns hunting with it. That went to one of my cousins. He mentioned my Grandmother’s bible in which she had recorded the entire family history. The Bible went to another cousin. And he wanted at least one of the rocking chairs from the porch.

Paul returned from the funeral with a story and a rocking chair strapped to the top of his car. He delivered the rocker ceremoniously to Dad, telling the story with his typical embellishment. According to Paul, his father, Uncle Jake, didn’t want to give up the rocker, and I never knew exactly why. Paul said he insisted, saying “I’m not leaving without a rocking chair for Uncle Louis!” He made it all sound heroic, and maybe it was. Uncle Jake was a stubborn man. But Paul wasn’t about to return empty-handed and was proud to deliver at least one of Dad’s requests to his favorite uncle.

That rocker first occupied my parents’ living room in Stockton, then in their retirement home in Murphys, and finally in their mobile home in Lodi. This is the last picture I have of Dad sitting in that chair.

Now it sits in my living room, looking slightly out of place. Someday I will add a southern-style porch to my Chico home, and maybe when I finally actually retire, I’ll make rocking chairs in my shop and sell them as a cash crop. Yeah, that’s the ticket.

Apparenly, I have been preparing for this for some time. Below is me rocking in my first rocker, contemplating the future.

The part about the front porch is at the top in the New Urbanist hand book, Reconizing the front porch is the social room and connects peoiple to each other and the street. When done well they pull from the isolated back yard oasis, When combined with other urbanist principles the porch is located close to the side walk and the side walk has very few curb cuts because most cars park in the rear. There is nothing new about New Urbanism, its more like Old Urbanism unforgotton. Interesting how a porch can provide beautiful memories and how we long for it without really understanding what we lost. Nice Story

Thank you for sharing this 'slice of your life' with us. Very interesting and also great photos.