Objects-The Shadowbox

A display of authenticity, save one.

I have one shadow box in my home. It rests in an alcove built into the bathroom wall. For that reason, I see it often. I made the frame out of oak. It measures about 12 x 24 x 6 inches deep. It holds objects of great meaning to me. Let me tell you why.

At the top is a picture of a man in his early 30s wearing a WWII navy blue wool tunic and a white officer’s cap with a black bill. Below and to the right is a military medal. To the left is a gold ring with a red stone. On the lower left is a gold watch with a braided leather bob. That watch is the only fake item in the box.

In his 20s, Louis Needham Berry joined the Navy. After San Diego boot camp, he was assigned to the Hospital Corps and, shortly afterward, was stationed at Pearl Harbor Naval Hospital. While the bombs were falling and torpedoes exploding, he was rushing back to Pearl from leave. He spent 7 days in a row caring for burn victims and the dead, without sleep, he says.

Sometime later, he returned to San Francisco and was stationed at Treasure Island Naval Hospital. While there, he was asked to take a test needed for promotion to the rank of Chief Petty Officer, a non-commissioned officer rank equivalent to a Sergeant Major in the Army. Decades later, he told me a story about that promotion.

Every Navy ship needed a Chief onboard, and towards the end of the war, there was a shortage of NCOs. As the war in the Pacific wound down, battle groups gave way to transporting troops and equipment. When naval warfare hostilities in the Pacific ceased, and later when Japan surrendered and its wartime territories were liberated, Japan was occupied predominantly by American troops.

After leaving Pearl, Dad was working at Treasure Island and socializing with some of his Navy friends in San Francisco, waiting for their next assignment at sea. He was approached by an officer asking if he and four others would take the test to be promoted to Chief. Transport ships were awaiting a full crew complement, and many were missing Chiefs. Maybe the Navy was desperate, though all qualified for the test, or perhaps it felt it needed to hedge its bets to ensure they all passed the first time.

Whatever the reason, at some point before test day, they were all given the answers to the test. When the answers were handed over, they were given a stern warning. “Now, you guys don’t miss all the same questions. It’ll make me look bad.”

After his promotion, the new Chief was assigned to a troop ship, the USS Dawson, an attack transport that sailed in the Pacific at the tail end of the war, and after the war ended. In addition to its role in Project Magic Carpet, transporting military troops stateside for discharge, after decommissioning in August of 1946, a month later it survived not one but two nuclear blasts in the Bikini tests, finally to be sunk off the coast of San Francisco as a gunnery target. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Dawson

The only time I saw the look on my father’s face similar to the one of him posing in his new uniform was when he posed for a similar picture decades later in his San Joaquin Deputy Sheriff’s uniform. A vivid memory of this woolen tunic hanging in his closet is still with me. I was fascinated with the embroidered insignia on the sleeve: a perched silver eagle above the red chevrons and rocker. Inside of them was a ranking mark for the hospital corps, a caduceus, the staff and serpents of medicine. That old Chief uniform jacket hung in his closet until he died.

Sometime after the war ended and he was back in San Francisco living with my mother, who moved there from Mississippi, he received a victory medal for his service during the war. It came in a blue cardboard box, which he kept in his bedside table for as long as I can remember. After it disappeared, it was returned to me by Dad’s neighbor. How he got it, I never knew. When he gave it to me, the box was tattered and falling apart. I saved the label from the end of the box, and placed it just under the medal. It reads

MEDAL, CAMPAIGN & SERVICE

VICTORY WORLD WAR II

This is the “World War II Victory Medal,” authorized by Congress on July 6, 1945. It was awarded to all military personnel who served between December 7, 1941, and December 31, 1946. There was no combat requirement.

The ribbon the medal hangs from is red in the center with rainbow edges, representing the global victory and hope for peace, inspired by the Victory Medal of World War I, which also used rainbow colors symbolizing a united Allied effort.

According to government records, the female figure on the front symbolizes Liberty, and she is wearing the armor of war, holding a broken sword and a broken staff, representing the defeat of tyranny and fascism. On the back are engraved the following words:

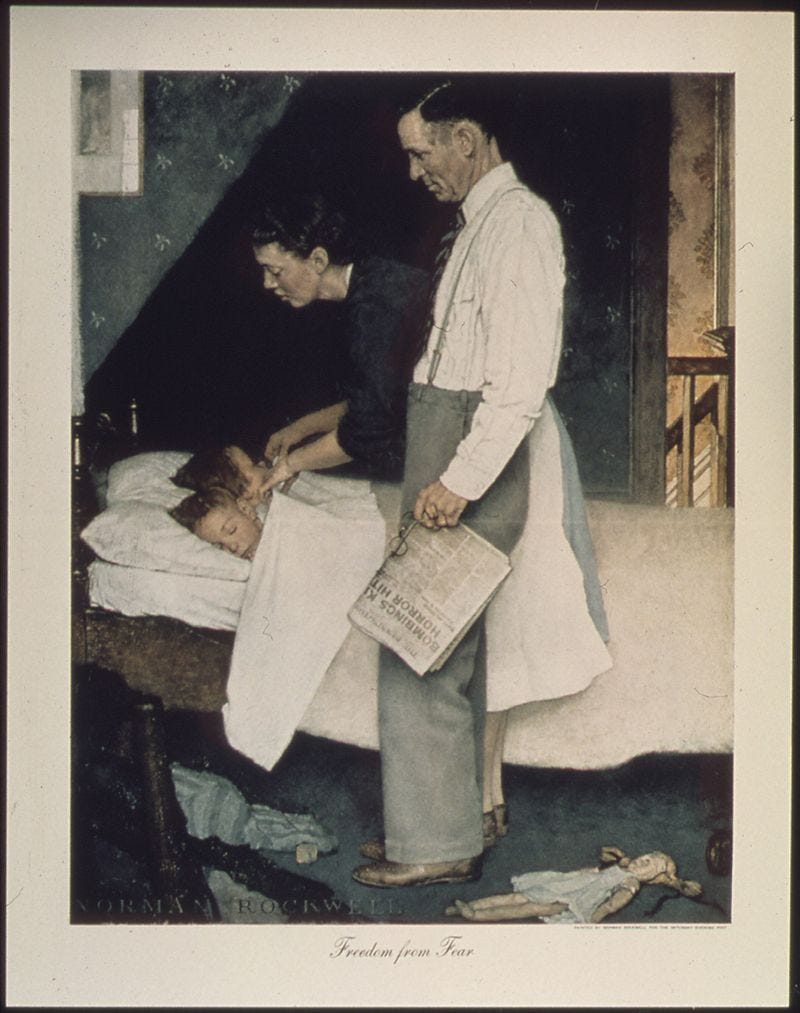

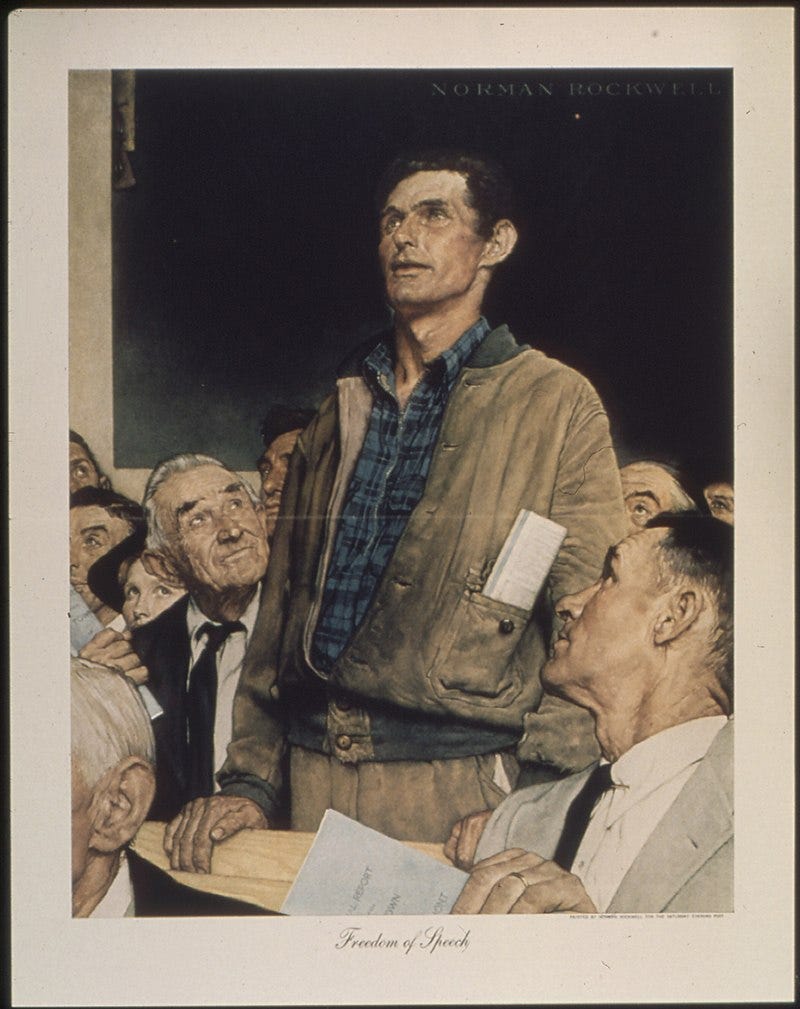

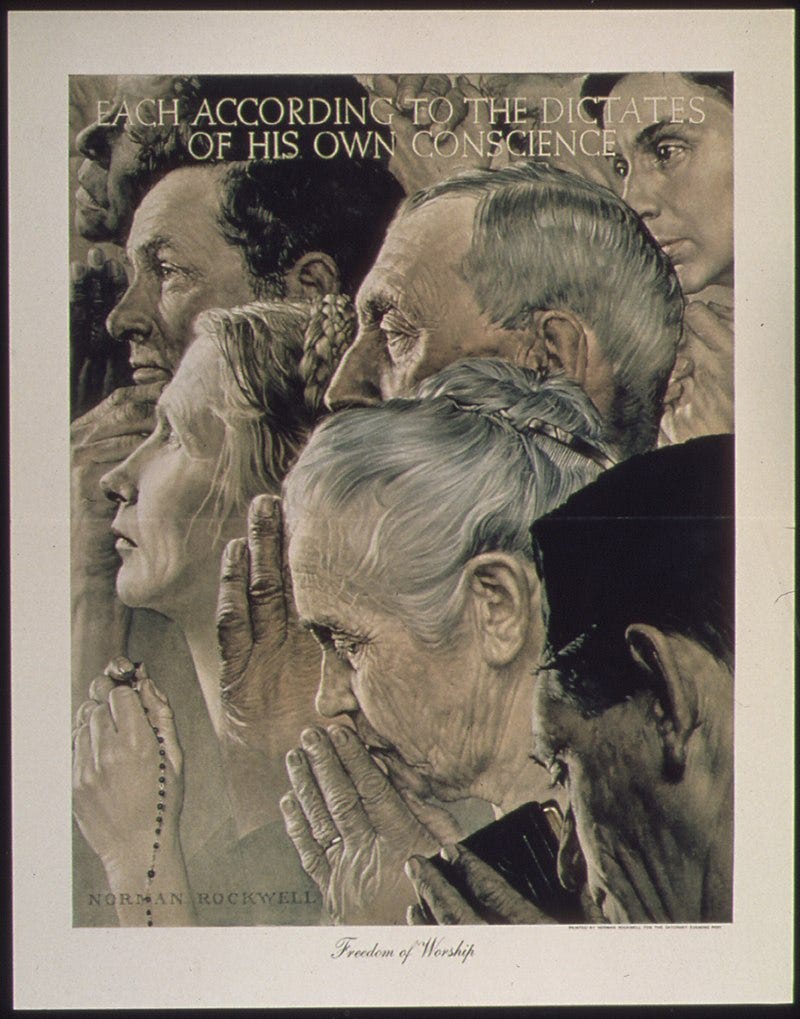

FREEDOM FROM FEAR AND WANT

FREEDOM OF SPEECH AND RELIGION

This language was inspired by FDR’s "Four Freedoms" speech and reflects the ideological victory he spoke of on January 6, 1941, during his State of the Union Address to the 77th United States Congress. It was a pivotal moment in American rhetoric, laying out a vision for the world that the United States should help shape — even though at the time of the speech, the country had not yet entered World War II.

This speech inspired the Four Freedoms series of paintings set by Norman Rockwell in 1943.

Almost in the middle of the shadowbox is a gold ring. I recently saw the Tom Hank movie “Greyhound.” It’s about a sea battle between his destroyer and a German submarine, and his ring looked exactly like the one in the Shadowbox.

The center of the gold ring is a red diamond-cut garnet or synthetic ruby, symbolizing valor, courage, and sacrifice. Surrounding the stone are the words “UNITED STATES NAVY.” On the shanks to either side are the familiar Navy insignia of the rope and anchor. The rope symbolizes unity and connection to the sea, and the anchor represents steadfast service. He likely bought this ring after completing naval boot camp in San Diego, a popular tradition.

Here is a story about that ring.

Dad rarely wore it, unless he was dressing up. He gave it to me when I was a young, post-pubescent teenager. I had little sentimentality to attach to that ring. It just looked cool. In junior high, I discovered girls. I gave that ring to the first girl I asked to go steady. She wrapped the back of the ring with dental floss and painted it over with nail polish to make it fit her skinny finger, as girls were once inclined to do.

Luckily, it was a short, innocent romance, and I got the ring back. I placed it in Dad’s cufflink box, where it remained until he died. I also avoided any future temptation to “go steady.” He would occasionally remind me that he gave it to me. I suspect those reminders were his sentimentality showing itself. We agreed to keep it in his cufflink box for safekeeping. After he died, it ended up here in this box. It made quite a journey from San Diego to my shadowbox.

We now turn to the watch.

Dad graduated from high school in Mississippi in 1934. As a gift, his father gave him a gold watch with his name, “Louis,” engraved on the back. When I went away to college shortly after high school, he made a little ceremony of giving me this watch. It was very old-timey and beautifully preserved. It didn’t keep good time anymore, so I had a jeweler clean the motion. It ran fine after that. The graceful cursive longhand engraving in the style of Dad’s handwriting is a long-lost art. Not only is it not widely used anymore, but youngsters say they can’t even read it.

When I moved to Chico in the early 1970s, I was a hippie. Like all “joiners,” hippies had a uniform. It consisted of expensive hiking boots, denim pants, and an embroidered snap-up blue work shirt. Personalized embellishments were then added. I chose a wool cap like my loyally followed comic strip character, Andy Capp. Andy also wore a scarf, but I wore a vest to complete the look.

If I still wore that hat and vest today, I would probably look a lot like Andy Capp. I bought the vest from Goodwill. It has a perfect place for a pocket watch, and being the problem-solver I am, I knew of the perfect pocket watch to put in my vest pocket. This completed my “conforming” but “personal” ensemble, a fashion statement that shouted “me!”

I wore that hat to threads, to the point where, on one visit home, my mom threw it in the garbage. I had to insist she tell me where it was. When she said “garbage,” I couldn’t believe it. I immediately retrieved it. That was a key part of my “look,” you see. “I’m not one to give up on a garment just because it has a little wear on it.” (H/T Lonesome Dove)

I would have laughed dismissively back then at the thought of my vanity. Vanity wasn’t cool. That’s why we “dressed down” like the earth people we pretended to be. Time always has the last laugh.

I carried that watch in my vest pocket for about a month before I started getting worried. By then, I had come to better appreciate what it meant to Dad and to me. During one trip from Chico to their home in Murphys, I spoke with Dad about it.

I told him I’d been carrying it with me wherever I went but was concerned I might lose it or maybe have it stolen. We made a deal. “You keep it safe for me here, and I’ll get it from you when the time is right,” I said. We both understood when that would be.

Upon returning to Chico, I purchased a cheap pocket watch from a gift shop to use instead (just switching watches, not giving up on the “look”). For years afterward, when I visited home, I made a point of checking on the watch in Dad’s open cufflink box on his dresser. While he was alive, I would never have asked for the watch. It would be like saying, “I think you are going to die soon.”

Eventually, I finished growing up and finally gave up the “look.” I added my cheapie watch to the collection of other watches on Dad’s dresser.

With time, Mom and Dad got very old, as parents sometimes do. Their mental conditions became forgetful, but I promised Dad I’d never move them out of their Lodi home place before he died. I took a solemn oath on that. It got to the point where a caregiver had to be hired. We went through a few.

Sometime in that period, I noticed the watch was missing, so I asked Dad about it. He had no idea where it was. He thought the worst. Dad was pretty short on memory at that point. Its whereabouts remained a mystery until he died. I thought we might never know where it went or who had it.

Mom was moved into a “home” in Livermore after Dad died, close to the home of my younger sister. It fell to us three siblings, my sisters and me, to go through the stuff in their mobile home. My wife of late was there too, and my younger sister’s husband. We were all going through the rooms, then checking with each other about what we found.

My wife and I were going through Dad’s desk. It was modern junk, but it had lots of hiding places. I was cleaning out the drawers on one side, and she was on the other. On her side of the desk, at the very back, was a space filled with junk. Tucked in the far corner, she found something in a leather pouch. She pulled it out and pulled the contents out to show me. It was the missing watch. I recognized it instantly. In her excitement, she carried it into the bedroom to show my sisters what we’d found. I never saw it again.

Things were a bit strained by then, and the sister team took over all important decisions. As the final gesture of “settling up,” one day, I got a box of things from my parents they thought I should have. That’s kinda how things were decided in our family from there on out. Among the stuff that meant nothing to me were two items that did. One was the Navy ring. The other was the cheap watch. That was supposed to be the consolation prize, I guess. One of them kept the real one.

What I believe happened was that Dad was concerned about the watch disappearing. I think he got paranoid when caregivers started spending the night. He might have remembered I was concerned about losing it. I think he hid it away in the back of his desk so no one could find it and steal it. Then he forgot all about it.

When I was making the shadowbox, I held the cheapie watch in my hand. It had something trivial to do with me but nothing at all to do with Dad. If the right watch was in the shadowbox where it belonged, this story would end differently.

Instead, it ends with a fake, a fraud, residing in a place reserved for authenticity. There it sits, and now you know.

As I said, I look at these shadow-boxed objects several times a day. Sometimes my thoughts linger on the ring, other times the medal, or the proud man in the new uniform. Each time, I have only warm feelings thinking about the man who once possessed these things. I don’t feel that way when I see the watch.

What a wonderful story Rob! Thank you, we probably all have saved objects with great meaning, a couple of mine are very similar that I view daily. Mine are old blued steel, not gold.