Social Change and Catastrophe Theory

An obscure mathematical model describe the "Great Awakening" Turn

The ultimate test of a writer is taking a complex idea and rendering it understandable to a general reader. Here goes.

As members of our contemporary society, we are experiencing one of the most dramatic periods of change in my lifetime, if not in human history. But then when things affect us personally maybe it just seems that way. As we feel the tension build, we also experience that tension as increased anxiety, and that’s natural too. When we see the potential for some form of chaos threatening to upset the stable present, we feel anxious, and that serves to motivate us to be on guard and get ready to act. It’s a survival thing. It’s a feature, not a bug.

Another thing to consider is captured in the concept of “fractals,” where patterns on the smallest to largest scale share similar if not identical patterns. Fractals are an analogy for the idea that political dynamics happening on the global scale display similar patterns at the national scale, the state, the county, the city, the school, the family, and between our ears.

That’s a good thing because if we can see the pattern at one scale of perception, we can know something about the other scales of the structure. “That is a useful bit of data right there,” as Ron White might say.

The one thing every level of societal structure has in common is human beings. Because of what people like Marx didn’t acknowledge but our founders did, human nature is immutable, it doesn’t change over the eons, and it can’t be “perfected” by better government institutions. It is always a personal struggle to become a “better” human being, and social institutions merely provide the guardrails for how “badly” we can act before we are constrained.

The patterns of human nature repeat not only across scales but also time. This might explain why James Madison wrote, “If men were angels, we wouldn’t need government,” which is still relevant today. Humans are still not angels, and some form of government is required for civil society to balance the tradeoffs between rights and obligations, freedom, and liberty. That is no easy trick, and we have been at it in America for a couple of centuries.

One aspect of history that constantly repeats itself is the ever-present patterns of change. We mostly experience change as slow and incremental over long timeframes. Every so often, this pattern is punctuated by rapid, sudden, catastrophic change. Maybe while we were focused elsewhere, the changes we were unaware of were the ones that powered the catastrophe, and it takes us by surprise.

The ultimate social catastrophe is war, and we know that wars don’t break out overnight. But we also don’t always see or understand the incremental changes leading up to that catastrophe. There is a long period of “peace” while the forces of war gather steam, then like a spark igniting gasoline, bullets fly, and bombs explode.

But short of war, or sometimes in conjunction with wars, dramatic changes to society itself can come on as a catastrophe, whether that turns out to be good or bad in the long run. Catastrophe theory is one way to talk about this kind of dramatic change, but as I do, remember that a sudden change that affects everyone is not about good or bad, right, or wrong. It is about the pattern and timing of catastrophic changes. They may be big or small, good, or bad, but they always follow a defined pattern, and always follow the same sequence.

Earthquakes are one example. For as long as you can remember, nothing. Then one day, Kaboom, a major earthquake lets loose, and many people are affected by the destruction. The death toll and destruction that recently took place in Turkey were a catastrophe in more ways than one. Earthquakes that cause such damage are eons in the making, but most of the time we don’t even notice.

Not all catastrophes are monumental disasters, but all catastrophes follow a pattern that can be described with mathematics. The catastrophe model applies to any slow process of change that ends in a sudden event that dramatically rearranges things. When it’s over things settle back down, though perhaps a little worse for wear.

Newton Discovers Gravity

A simple example is Newton’s famous apple acting under the force of gravity. Both he and the apple became famous when he noticed that apples never fall up, only down. Gravity always works in only one direction, like time. Things never fall up, except for the occasional President. Because Gravity is so predictable, we can create models that explain what is happening. Let’s apply our catastrophe model and see how it works.

There’s Newton, chilling under an apple tree. His apple is firmly attached to the tree by its stem. But as the apple ripens over the months, it grows heavier, and the stem begins to dissolve at the joint. That small and subtle change makes the coming event inevitable. After defying gravity all season, in an unpredictable instant, the stem gives way to the force of gravity, and the apple begins to fall. If it starts from high up in the tree, it falls farther than one lower down. How long it falls becomes its history, and that becomes important later on.

When it finally reaches the ground, it is traveling at a speed based on its history. The delay between when it started falling (cause) and what happens when it hits the ground (effect) is called “hysteresis,” the delay between cause and effect. How hard it hits is a function of its history. Higher means faster, and faster means it hits harder.

When it finally does hit the ground, all the speed (energy) it gained on the way down is transferred to the ground in one direction and to the apple in the other. Depending on how much “give” there is in the ground, the apple might gently bounce, or make a “splat” that destroys it. Only one might be a disaster for the apple, but either way, it is a pattern of catastrophe; a) a long stable period, b) a point of divergence from the stable state, c) an inevitable consequence is set in motion, d) a sudden release of accumulated energy, and finally, e) a return to a steady state.

That pattern applies to any number of natural phenomena, including falling apples, landslides, earthquakes, plane crashes, and volcanos, and here I am trying to convince you it applies to politics. I was never very competent in math, so I’m going to use words and pictures to try to explain.

Catastrophe Theory Model

Imagine the stable and predictable world around you as a flat piece of paper. All your friends and family are standing with you on that same piece of paper, near one edge. We can call this surface the “behavior surface.” The paper is moving under your feet in the direction of time, so behind you is your history, and in front is your future. We experience our lives playing out on this surface, moving forward with time. Time only goes in one direction, so we can never “walk” backward, only forward. This is a simplified representation of “life” as a mathematical model.

The amount of time we spend on the “behavior surface” living out our lives is our history. This is one way to visualize a simplified model for the course of events in our lifetime. But we don’t expect the surface to remain “flat” or free of catastrophes forever. As the saying goes “Stuff happens.” (unlike Forest Gump, this is a family show)

We begin with you and all those around you on this “behavior surface,” which we visualize as a piece of paper, flat and uniform in all directions. That is the steady state when your life is stable, predictable, and mostly the same from day to day.

Then one day something catastrophic happens, and the world as we know it suddenly changes. How do we describe that? Did we fall off the edge? Did the paper tear in two? If we are still around, we must be standing on something. The explanation is Catastrophe Theory.

Okay, now stick with me. Don’t go all shark-eyes on me just because I’m going to show you a diagram you don’t understand yet. This is the challenging and fun part.

Diagram of Catastrophe Theory

Here is a simple diagram of the catastrophe model. There is math behind this, but let’s not bother. Focus on the “Behavior Surface” and ignore the rest.

You can see that the paper didn’t tear, and we didn’t fall off the edge. It folded in such a way that there was a difference between the surface of the paper above the fold and the surface below. That gap, represented by the size of the fold in the paper, represents the magnitude of the developing catastrophe. That magnitude is a function of history, that is, how long it was and what happened between that first moment of divergence, and the sudden change of the catastrophe.

That delay between cause and effect, based on the history in between, is called “hysteresis.” The longer the delay, the longer the history, and the more time the catastrophe has to build up steam. So, the magnitude of the catastrophe increases with time. To use a trivial illustration, the longer you force water into a balloon, the wetter you will get when it bursts.

As a general rule, the longer the history after divergence, the larger the consequences of the catastrophic event. After the moment of divergence, we are no longer on a flat, two-dimensional sheet of paper, but a 3-D surface that can be folded.

Earthquake Example

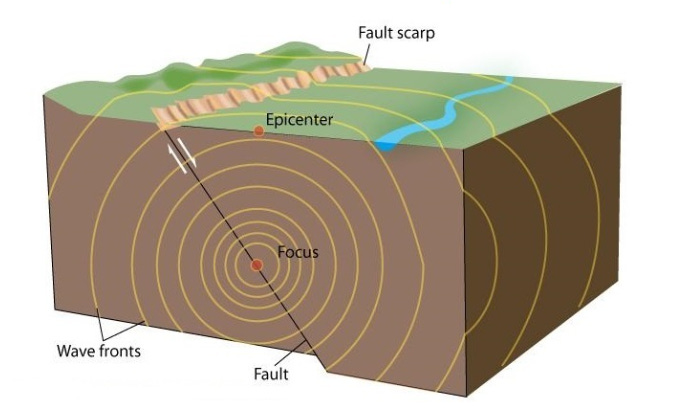

Now imagine this model is describing an earthquake, a specific type of catastrophe. The one I remember was in 1989. For all your geology drop-outs in Rio Linda, the earth’s crust is about 25 miles thick and composed of floating plates that grind into each other at the edges, or one passes under another and melts back into the molten core of our planet.

We call these things “tectonic plates” and there are only 7 of them on earth. They are huge and they move, so you can think of them as sheets of thick ice floating on a liquid ocean. This movement is responsible for volcanoes, mountains, and earthquakes. Where two plates come together, the edges meet with tremendous power and friction. A certain amount of energy is required to overcome the friction along the fault line where they collide.

Now imagine when the two plates first come together in some distant time in the history of Earth. At first, they are just touching each other gently as they meet for the first time. As soon as they begin to push against each other, we can say that is the moment of divergence between when they didn’t “care” about each other, and when they began resisting the other’s movement. Before the divergence, there is no energy accumulating in the fault, but once they start moving against each other, the outcome will inevitably be an earthquake. There is no undoing that outcome. It is just a matter of time, and the more time, the greater the eventual magnitude.

This is because the magnitude of an earthquake (catastrophe) is a function of its history, encompassing the years they were pushing against each other and accumulating energy in the fault. All this while on the surface, we experience nothing new, the “paper” remains “flat,” but in reality, the paper world is beginning to fold as the plates silently interact. How we experience the consequence of that interaction depends on where we are standing the moment the earthquake appears.

Using the language of our catastrophe theory, starting from that first moment of interaction between the plates (divergence) the longer the time that interaction takes place (history), before the catastrophe, (earthquake), the more powerful the effect (magnitude). The length of the delay between cause (plate movement) and effect (earthquake) is the “hysteresis” of the fault system. For a major earthquake, that might be measured in millennia. See, you are thinking like a scientist now.

Meanwhile, while all of this is happening under our feet, we are safe from earthquakes and volcanoes or mountains suddenly rising. The plates are silently and invisibly storing energy along the fault, and our lives march merrily along without notice.

One day in an instant, when the friction along the fault can no longer resist the force of the moving plates, the earth quakes, destructively shaking us and everything around us. We can’t help but notice. But for the millennia leading up to that moment, for many generations, humans were free to act as if nothing important was happening. We lived our lives as if an earthquake was never going to happen, and we were mostly correct, right up until “earthquake day” when the truth became undeniable.

The scale of change affecting earthquakes and humans is very different, but because we know about fractal patterns, we also know that the pattern at the geological scale has something in common with changes on the human scale.

Social Catastrophes

Now we have what we need to better understand our diagram in the context of social catastrophes. We start our journey with everyone living on a flat sheet of paper as time marches calmly and unremarkably forward. Then, almost unnoticed we come to a point of divergence, some subtle change that causes some people to move toward the left side, and others to move toward the right side. Almost imperceptibly, the two sides begin to separate, divided by the growing “fold.”

At first the “fold” between the two sides, just past that point of divergence, is small. Both sides can still see what the left and right sides are doing, and we can still communicate, and maybe even move from one side to the other. As time and history continue, the size of the fold continues to grow.

At some point, those on the lower part can no longer see the upper surface, and since they can’t go backward in time, those of us on the left and right sides are separated and can no longer see or reach each other. We can no longer communicate as we once did.

In our diagram, this is labeled the “inaccessible” region, first appearing when the history is long enough, and the fold is sufficiently advanced so that the “fold” creates a barrier between the two surfaces, top and bottom. There is no way to predict when the catastrophe will strike, but the fact that it will come eventually is inevitable. According to the model, the fold cannot continue to grow indefinitely. At some point in time, the power of opposing forces equalizes, then flips, and the catastrophe appears.

Sometime before the catastrophic event, imagine we are on the top surface looking towards the gradually sloping, top surface of the fold. We cannot reach those below without “falling” off the edge to the surface below. That would be a personal catastrophe. For those on the bottom we can’t reach those above because by now, the sides of the fold block our way. We are stuck where we are. Maybe once in a while, we see someone falling from the sky and wonder where they came from. Unfortunately, they don’t survive the fall, so we can’t ask them.

One group of people now lives on the “upper” surface, and the others live on the “lower surface.” The top and bottom are separated by a “fold” but are still part of the same “world” that is represented by the surface of the paper. Maybe after a very long time, we even forget the others exist.

As long as the fold keeps us separated, neither side seems affected by the other. But we know this is not true, because the “energy” that separates the two, much like the fault line in our earthquake example, are working in opposite directions on the same “world” and we know that the fold will not continue to grow forever.

Eventually, the two levels of the surface will collapse upon one another, returning the “world” to the flat, featureless sheet of paper it was before the divergence. This “rejoining” of the parts of the “world” is inevitable, just like an earthquake is an inevitable consequence of fault lines. Sooner or later, when the “force and friction” balance, then tip in the other direction, that stored-up energy will be suddenly released. That sudden release of stored energy is a catastrophe by definition.

Catastrophe Theory Thought Experiments

We can invent our own thought experiments by imagining ourselves standing at various points on this diagram or thinking about various ways to describe a point of divergence based on specific events. We can consider the history during the “silent” time in between and what “effect” finally appears as a catastrophe, born of the original divergent “cause.”

When we are on the flat part, before a point of divergence appears, we can see everything else around and the world remains generally the same from moment to moment. No part of the world is hidden from view. Our movement from side to side is free and unencumbered, and the future is predictable.

When we imagine ourselves in the territory well beyond the divergence point, we can see that our world is smaller than it was before because the “fold” divides what was once a unified world into two separate regions, one above and one below the fold, and one part of the “world” remains hidden from the other.

The world might look different from above and below, but you can’t understand what you’re seeing unless you can see both sides at once, and from inside the model, that is impossible, just as it was impossible to understand the “silent” phase of an earthquake before we developed a model to explain it.

The Physics of Catastrophe

Now don’t get all blurry-eyed just because I wrote the word “physics.” You can do this.

What happens to our model in the moment of catastrophe? Just before that moment, we have some people on top and some on the bottom, separated by the fold. The size of the fold, and the height of the “inaccessible region” is a measure of the potential difference between the upper and lower surfaces.

That difference is a function of history since the point of divergence, and the delay between that original cause and the eventual effect of the catastrophe is the hysteresis of the system. In other words, the “divergence” is the initial condition that eventually produces the catastrophe, and there is a long delay between the two. To capture the idea poetically, the beating wings of a butterfly are the initial condition that eventually produces a hurricane.

In our social thought experiment, neither those people on top nor the bottom can tell how big the fold is from their perspective on the surface. For each, the surface they are living on is flat and featureless. For those of us on top, we perceive the fold as a cliff we can’t approach without “falling off,” and for the bottom people, we perceive it as a curving wall that bends back over our heads. But all of us are standing on flat surfaces, just like we were before the point of divergence.

The laws of physics say that all systems seek equilibrium, and the differences among various parts eventually return to zero. That is called “entropy” but let’s not worry about that now.

Let’s agree that catastrophe systems behave in the same way, whether an earthquake fault or any other natural system. It starts at zero difference, accumulates energy in one part or another, and eventually equalizes. A catastrophe is how a system suddenly returns to equilibrium.

Catastrophes are relatively sudden, unlike say the gradual mixing of two inert gasses. Catastrophes are a snap of time compared to history and happen dramatically. Earthquakes, landslides, and civilizations rise and fall over time. In our social catastrophe thought experiment, we know that a catastrophe must return a system to equilibrium between the top and bottom surfaces of the “world,” but how does that happen?

The catastrophic collapse and rebirth of the “World”

If we can imagine this in our mind’s eye, just before the catastrophe, we are standing on a flat surface above or below the fold. For all we know, the world we see around us is the only one that exists. But according to our model, there are two parts of the world, one above and one below the fold. Each thinks their world is all there is. But the differences, which first appear at the point of divergence, grow over time, represented in the model by the vertical height of the fold.

At the moment of catastrophic change, the top surface of the fold “collapses” downward, and people standing on the upper surface go into free fall. You already know what happens to Newton’s apple when it hits the ground. For those below, the “ceiling” of the fold collapses on them, and they get squashed.

This collapse can be sudden, like an earthquake, or prolonged, like a hurricane, a forest fire, or a war. But all follow the same pattern and sequence.

The good news

We will have to look carefully for any good news in the aftermath of a catastrophic change. Those of us standing on the edges of the paper “world” escape the destruction, but like “timing the market” we can never predict where it is safe to stand. Some guesses might be better than others, but by the nature of catastrophes, though we might guess the “what,” we can’t tell “when.”

Assuming the catastrophe doesn’t destroy the entire world, some of us will find ourselves in a “new world,” as the two parts of the world become visible, and once again returns to a single, flat surface. As we look across the expanded landscape of this new world, we see the destruction the catastrophe left behind. Some of the things and people near the fold are no longer with us, and much of what they had built is destroyed. Catastrophes do not happen without consequences, but they never seem to destroy the entire world. If they did, we wouldn’t be here to care, like the dinosaurs.

The good news for whoever survives, we now have a reunified world to work with, and we can all work together to rebuild something better. Apparently, we’ll have about 100 years to try. This is the nature of “The Fourth Turning” described by William Strauss and Neil Howe, the 100-year storms that have affected societies periodically throughout the history of civilizations.

Perhaps we can learn something from our catastrophe model that might help us do better next time.

Avoiding Catastrophe

The “potential difference” between the top and bottom surfaces is measured by the size of the fold. The wider and taller the fold, the greater the difference between the top and bottom surfaces, and the bigger the impacts of the resulting catastrophic change.

At the instant before the moment of divergence, there are no differences anywhere along the surface. The moment a divergence appears, the “catastrophe fold” is at its smallest, but grows larger with time. We know if too much time passes by, if the history after divergence is long, the world becomes irrevocably divided and the future catastrophe will be larger, inevitable, and unchangeable.

Catastrophes, remember, are defined by a sudden change, not by the magnitude of destruction. If we could, the way to avoid big earthquakes would be to continually “bleed off” the energy in the fault with tiny tremors that cause no serious destruction. By releasing the energy of the fault in small increments instead of devastating monster quakes, much destruction could be avoided. Unfortunately, we don’t know how to do that, so we wait and see what happens.

Also remember, at the moment of divergence, those on both sides of the “paper” could see each other without obstruction, because the differences on either side of the fold are small. If we are talking about people, individually or collectively within a given social structure, we could say that catching the moment of divergence and “bleeding off” the energy is the way you avoid social catastrophes.

Figuring out how to do that seems better than letting the catastrophe build and suffering through whatever happens later. On the other hand, ignoring divergence ensures that the inevitable catastrophe will be large and destructive. This applies equally to fault lines, politics, interpersonal relationships, and personal growth.

If our fault line was slippery and released energy in tiny increments, each of those releases would still technically be a mathematical “catastrophe”, but their impacts would be small. The longer the time after divergence, the more energy accumulates, and the larger and more destructive a catastrophe will be when it finally comes.

If a married couple adopts a policy to never go to bed mad at each other, to resolve the divergent issue right away, the major catastrophes of marriage might be avoided, even if it means a few sleepless nights.

If political parties worked together in good faith and compromise, well, you get the idea.

In every case of divergence, a point of no return is reached if differences are left unresolved. When the divergence reaches a certain point, represented in the catastrophe model by a deep fold in the paper, there is no turning back, the size of the catastrophe can no longer be moderated because interactions between the divergent sides are cut off by the “fold,” awaiting the pending disaster.

Some marriages are doomed to failure long before divorce papers are finally filed. In retrospect, couples are often capable of recognizing when the trouble first began, when the marriage partners began to diverge.

Wars between nations can often be traced back to a specific moment of divergence. The assassination of Duke Ferdinand might be such a moment before WWI. At least it seems that from that moment forward, there was no way to stop the inevitable.

In the political realm, it is much more difficult to pinpoint the point of no return, but the fact that we are beyond intervention or reversal seems self-evident. Quite literally, the divergent sides are not communicating in good faith or compromise, if they are communicating at all. We know we are beyond the point of no return when it is impossible to unwind the forces building toward catastrophe.

Timing the market and predicting catastrophe

All sophisticated investors understand that it is impossible to “time the market.” That is, no one can tell precisely when a market has “peaked” just before it collapses into lower prices. You may be able to see the direction a market is headed, but you cannot determine the timing of changes. This is due to hysteresis, the indeterminate delay between cause and effect. The more complex the system, the more impossible prediction becomes.

The importance of this idea is that while we can say that cause will always produce an effect, it is much more difficult to say when. In our personal lives, we experience this all the time.

Someone does something in a relationship that eventually breaks up the marriage, but the actual break-up might be years in the making. The Civil war might have begun with Ft. Sumter, but the divergence between North and South began decades earlier. What was the moment of divergence that led to WWII? Was it Hitler’s invasion of Poland in 1939, or was it the signing of the Versailles Treaty twenty years earlier? It was known by many that war with Germany was inevitable, but no one could say when.

In any context we can imagine, we may realize we have reached a point of no return, where reversal or reconciliation is out of the question. But knowing when those consequences, the inevitable catastrophe will appear, is another question entirely. There is a delay between cause and effect of an unknowable duration, and we name that delay “hysteresis.” Every catastrophe has hysteresis as a feature, at every scale of perception.

As the saying goes, I only told you that to tell you this.

Society is a fractal structure made up of people, and patterns of human conduct and motivations repeat at every scale of perception and organization, whether looking upwards to the national government or international relations, or downwards towards local politics, the family unit, or individual experience.

What we are experiencing in our collective minds at this moment is a growing awareness of a looming and inevitable catastrophe, though we cannot know exactly what form it will take, or when it will arrive. That, my friends, is a perfect formula for anxiety, social, cultural, and personal.

We can hear the dragon roaring in the distance, but we have no idea when it will come or what will be destroyed, but we know its arrival is inevitable. Once awakened, the dragon must devour. So, we worry, and if we are wise, we prepare.

What we know intuitively is that we are well beyond the point of divergence, which may have occurred long before we were even born. Some consider that point sometime before the end of WWI. But at this point, it doesn’t matter what or when.

Our visibility of the “other side” is obscured, communication is nonexistent, and there is no avenue of escape. We can’t rely on what we hear or read, and we cannot see beyond the “fold.” We can only interact with those around us, on one side of the catastrophic fold. We know who they are because we can see and touch and interact with them. We know nothing of those “over there” on the theoretical “other side” of the world.

We perceive with growing certainty that we have passed beyond the point of no return, but do we prepare for an earthquake, a war, a famine, a pandemic, or something not yet imagined? If we apply the concepts of catastrophe theory, we know that tension will continue to build until that moment when the dam breaks, the earth quakes, the forest burns, or the bullets fly. We don’t know what it will be, but we’ll sure know when it comes.

By looking at the model diagram, we can see that we are either below or above the “fold”, cut off from what was once a flat, stable, and predictable world. Those times are behind us now, and we are powerless to avoid the looming catastrophe that lies inevitably ahead.

In the language of the book, The Fourth Turning, we seem to be approaching that long-awaited historical moment that punctuates history approximately every century. I happen to be, according to that theory, the oldest generation in the cycle that will experience world-changing events, assuming the last such event was WWII. We are overdue.

As a final point, let me try to leave you with some optimism, which may be difficult after my relentless exploration of inevitable catastrophes.

Preparing for Catastrophe

When catastrophe hits, what will we have to work with? That is difficult to say unless we know the nature of the catastrophic change. Some may think about the Camp Fire. It seems self-evident now that the point of divergence in that disaster was when we stopped managing our forests with small fires and lumber production. After many decades, a tiny mechanical failure wiped out an entire town, and our community of Chico was at the end of the escape routes, so victims came here. It was a catastrophe, and it changed our local world in dramatic ways.

If you were here at the time, you remember it well. For most of the victims of that catastrophe, the only thing they had left was other people, and for weeks and weeks, we witnessed the spectacle of people helping people in the course of an unfolding disaster of catastrophic proportions.

No one asked about religion or political affiliation before pitching in to help. It was a matter of principle, the compassionate side of human nature, and the pressing immediacy of disaster. At that moment, the part of human nature not separated by “divergence” came to the fore, and something fundamental took over.

If we were wise, we would realize that in the face of an inevitable catastrophe beyond our control, we had better prepare. When everything we have in our stable and predictable world is stripped away by forces we cannot control, what is left?

I would say there are only two things left: the immutable human nature, and the principles that guide us to act for the good of others, or the bad.

The first principle of civil society is the Golden Rule because doing for others is the best way to do for ourselves. That is the most fundamental principle of civil society, and that is the foundation upon which society was built in the first place, improving life and reducing suffering.

The problem is not that we find ourselves below or above the “fold.” A bigger problem, we are cut off from the means to avert the coming catastrophe. While we might be aware of divisions among us over issues like schools, land use, housing, “homelessness” and the impacts of drugs and mental health, or even the motivations and tactics of political ideologies, there is a deeper divergence that encompasses all of that, and it likely originated before most of us were born.

Our biggest problems today arose from that original, unmitigated societal “divergence,” tiny at first, but allowed to grow and grow over a very long period. Because this divergence by now has a very long history, and because of hysteresis, the power behind that divergence has been growing.

That means the impact of the looming catastrophe will be large. According to our model, we are by now beyond the point of no return, where future intervention is impossible, the two “sides,” depicted by the upper and lower “behavior surface” on our imaginary sheet of paper are inaccessible to one another.

We cannot know precisely where we are on the “catastrophe model” because we are experiencing it from the “inside,” so our ability to see the whole is limited. We do understand intuitively that there are those in our world that cannot be reached, or perhaps even be seen.

The only people we can see or reach or meaningfully interact with, are those “on our side of the fold.” What separates us from those on the “other plane in the world,” is the same forces that are feeding the power of the coming catastrophe. Each side contributes equally to their part of the “fold.”

When we scientifically speak of energy and power, we are not necessarily talking about individual people. We know that in society, a small number of people can control vast amounts of power, and many people acting together can also produce immense power. So when we think of the division in our “paper world,” we shouldn’t assume there are equal numbers of people above and below. A variety of combinations of numbers and power are possible.

Each will contribute somewhat equally to the catastrophe because that is the nature of physics and energy and change. To each group, those on the other level are “invisible,” pulling society in different directions, not side to side but up and down, and to the other, each will seem to be the “Invisible Enemy”. The invisible will only become visible after the catastrophic change when the “fold” dividing them collapses and the potentially destructive energy of the catastrophe has had its way.

A “turning point” catastrophe is not likely to be confined to the kind of damage of a local disaster like the Camp Fire. A “Turning” is something that no one in the world escapes. It changes everything, and like the 100-year storm, it is exceedingly rare. That rarity is what permits us to ignore it until it finally arrives.

In retrospect, historians will examine the “history” of the catastrophe and will debate various theories of when that point of divergence occurred, why we didn’t notice it earlier, and when the catastrophe reached the point of inevitability, the point of no return.

But that is not our immediate concern. What we need to understand now is where we are standing on the “behavioral surface,”, and where we are in relation to the point of divergence and the point of no return. Knowing that perhaps we can figure out how to prepare for the inevitable, turning catastrophe.

Also of concern, for future generations, can we learn anything about how to avoid or mitigate future catastrophes from our experience of living through one? That is the most important source of optimism and hope.

Preparation: the Big Picture

Because the focus of this article is the domain of social catastrophe, preparations are described in a social context. If you want to be a “social catastrophe prepper,” here are a few things to consider. We could:

Re-examine and familiarize ourselves with our fundamental principles, because when that moment comes, we will have to navigate through the chaos with those principles. It will be too late once we are in the midst of catastrophe to figure out what to do or why. Values and principles begin with “the Golden Rule” or “everyone for themselves.” Let’s be civilized.

Realize that those who share our most fundamental principles are on “our side” of the fold. You are best served by knowing who they are and making sure they know you. Those are the people we have to depend upon when the fan gets hit with you know what.

Form small groups of allies who share your immediate passions. Some of us are focused on schools and children. Build a virtual army around that. That same army can be called into action when a greater threat appears. Some are passionate about city government and so forth. Realize that no one gets to sit on the sidelines when catastrophe hits. Social networks are critical when you are in need and chaos reigns. Decide what issue you are most moved by and join with others moved by the same.

Practice being involved. The Bible prescribes 10% tithing, and common wisdom advises saving up for a rainy day. That is not just about money, it is about your time and your priorities for allocating it. Everyone who cares about themselves and about others needs to be on the field of citizenship, and at least some of your time should be devoted to that endeavor. Budget your time to leave room for citizenship. Citizenship is not a spectator sport.

Acknowledge that a vision of the future must exist before you can follow your dreams to get there. Visualize your future, the future best for yourself, your family, your friends, and your community. Drive a stake in the ground and don’t let anyone burn you at it. There are victims and victors. You can obtain the future you most desire, but you must first articulate what you want. It won’t come through legislation, that is the vision of a stranger. That vision starts with you and grows with others who share it. You belong here. It is ok to act like it.

Finally, what I describe here is not something that can originate from inside a social structure on the verge of collapse. It will happen through something I did not discuss, the “network effect.” This is the concept of decentralized networks that wonders like the internet are built upon.

The way it might happen, the way it must happen, in my humble opinion, is with individual people wherever they are. Look around in your own heart first. Resolve begins there. Then unify your family. If families are solid, healthy social units, the rest will follow.

You know other people who have families. Apply the effort needed to earn common ground. Now you have a small army. Commit to mutual aid and dependence. We see this happening at our local school boards, the lowest of all governmental organizations. Small cadres of people with shared values become forces of nature standing for principles that we inherited in our culture and traditions. All that is needed is to remember what they are and be willing to stand for them at some personal cost, even if that cost is only some time and a little extra effort.

Leadership is not something that originates “from the top” of social structures. Leaders are those who follow from the front of the crowd.

This was definitely one of your longer reads, notably well thought out. I appreciate your forethought to where we are and where we are destined, both locally and as a nation, it assured me that my own anxieties are not felt alone.

Thank you for sharing.

🤩..you always manage to evoke grins & giggles as you plunge the depths of cognition—humor that assure us that even you don’t take life

Too seriously. When you aim for the middle of your audience, you hit the 🎯. Somehow your gripping diatribe sucks us in to go the distance & read to the END. I’m not sure who is more enlightened, you or your audience for reflection is true learning.

Know that you do important work & that you have been chosen for such a time as this. CHICO shall forever be in Your debt.

WRITE ON.